Both the American Animal Hospital Association and World Small Animal Veterinary Association have recently published guidelines for the nutritional assessment of pets as part of routine physical examinations. The role of nutrition in animal health has long been a very important but often underutilized component of veterinary medicine. These guidelines recognize the vital role of nutrition in promoting optimal health and response to disease and will help veterinary practitioners use their training and skills in evaluating the nutritional status of their patients.

The interconnectivity of veterinary medicine and nutrition is not a new concept. The American Academy of Veterinary Nutrition, the very first allied association to the American Veterinary Medical Association, was founded in 1956 to facilitate discussions of mutual interest to veterinarians and animal nutritionists. The American College of Veterinary Nutrition was founded in 1988 to advance the specialty area of veterinary nutrition and increase the competence of those who practice in the field.

Of the 60-plus diplomates currently in ACVN, over three-quarters of them are primarily involved in small animal (particularly dog and cat) nutrition. Most of those are academicians who help train many of the newly graduating veterinarians, but a number are involved in the petfood industry as well.

The mission of AAHA is to promote and recognize high standards in veterinary practice and quality pet care, primarily in the US and Canada. WSAVA is described as an association of associations, a common global link for many veterinary groups. Its primary purpose is to advance the quality and availability of small animal medicine and surgery all over the world.

Both organizations are involved in many issues relating to veterinary medicine. With such full agendas, it is notable that nutrition has been recognized by both groups as a critical component of overall pet care.

The guidelines of WSAVA were largely based on those developed by AAHA, so they are very similar. Both association task forces that developed the respective guidelines included ACVN diplomates.

The guidelines emphasize a three-prong approach to nutritional assessment as recommended by ACVN in its “Circle of Nutrition” precept. Of course, nutritional assessment must include evaluation of the pet’s food. However, whether or not the food meets certain standards is only one component. Equally important are the individual nutritional needs of the patient and feeding management (i.e., how the food is fed to the animal). A deviation from the norm for any of these components could have significant nutritional implications.

The guidelines say a nutritional screening evaluation through routine history taking and examination should be conducted on every animal. Healthy animals with no nutritional risk factors may not need further evaluation, although animals in more demanding life stages (e.g., growth, gestation/lactation, senior) or conditions (e.g., very low or high activity, multiple pet households) may require closer scrutiny.

Specific risk factors in the history of the animal that may require an extended evaluation include:

- Altered gastrointestinal function;

- Ongoing disease or administration of medications;

- Feeding of unconventional diets or supplements; and

- Heavy feeding of treats.

Some factors found on physical exam that may prompt further evaluation include a low or high body condition score, evidence of muscle wasting, dental anomalies and poor skin or coat.

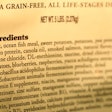

Evaluation of the animal’s diet looks at all components—not only the mainstay petfood but also treats, table scraps, supplements and chews. This includes review of the label information, particularly the Association of American Feed Control Officials nutritional adequacy statement and other mandatory labeling. Assessment of calorie content is considered a top priority, although it is noted that the labeling may not include this information. (As a side note, AAHA was one of the veterinary organizations that endorsed ACVN’s proposed amendment to the AAFCO calorie content regulations.)

The guidelines advise veterinarians regarding the role of labeling as “advertising” and to be cautious about unregulated terms such as premium, holistic and human grade. Unconventional diets (commercial or homemade) may require extra scrutiny. Veterinarians should also consider the manufacturer’s reputation, history and any objective (non-testimonial) data it provides to support use of the food and be willing to call the company with any questions regarding the product and its formulation, quality control and place of manufacture.

Foods suspected of being the cause of illness should be tested for likely contaminants. Veterinarians are urged to contact the feed control official in their state. The guidelines include links to AAFCO and FDA websites, as well as sites for many other sources of useful information.