“It’s complicated.” That’s how Louise Calderwood, director of regulatory affairs for the American Feed Industry Association (AFIA), described the current U.S. regulatory landscape for pet food manufacturers and ingredient suppliers in her “Petfood Insights” column coming up in the July 2025 issue of Petfood Industry magazine. That might be the understatement of the year.

For example, the landscape covers several pending (even competing?) new pet food ingredient approval processes, which Calderwood outlined in her column. (For background, we’ve previously reported on these, including the Pet Food Uniform Regulatory Reform (PURR) Act, a new Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) process in partnership with Kansas State University (KSU)-Olathe, the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) new Animal Food Ingredient Consultation Program (AFIC) and the Innovative Feed Act.)

Talk about complicated — just consider that alphabet soup in the previous paragraph!

Calderwood also mentioned the uncertain status of the Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) designation process for ingredients, especially so-called self-GRAS. That and the new ingredient approval processes were just two topics discussed at length by Calderwood and others during a closing panel discussion at Petfood Forum 2025. Their comments on self-GRAS may provide insights for pet food companies and suppliers.

Existing and new challenges to self-GRAS ingredient process

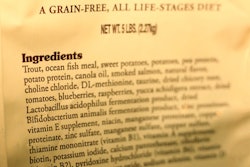

Self-GRAS has always engendered its share of criticism, concerns and confusion. “The self-GRAS pathway, enabled by a 1997 proposed rule and finalized in 2016, allows ingredient companies to voluntarily notify FDA of their GRAS conclusions,” Calderwood wrote. “Despite its intent to improve the efficiency of the regulatory process, the voluntary GRAS notification process has proven to be unduly burdensome for animal food, and to date, only 31 animal food ingredients have been successfully notified.”

During the Petfood Forum 2025 session, some of her fellow panelists expressed other problems with self-GRAS, including inconsistency among filings. “I've seen a lot of self-GRAS determinations in my life,” said Todd Harrison, partner and co-chair of the FDA Group at Venable, a law firm that advises clients in the animal and human food industries. “Some are extremely good, and you could file them tomorrow with FDA; it might take you two years to get through it, but you’ll still get through it. But I’ve also seen ones where I just I fell out my seat laughing, like you gotta be kidding me.”

Now adding to the challenges, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has directed FDA to consider rulemaking to end the self-GRAS process, Calderwood said, as he engages with Congress to explore legislative changes to do the same. “I've been told there are over 200 members of Congress that are supporting giving up self-GRAS,” she commented during the panel discussion.

“Secretary Kennedy seems to think that the problem with the food supply are GRAS ingredients, though he doesn’t understand that self-GRAS … is as rigorous as being FDA approved,” Harrison added. “He doesn’t seem to understand the ingredients he has this issue with were actually FDA reviewed and approved.”

Solutions on the horizon present their own challenges

The new AAFCO-KSU process will meet the requirements of FDA’s GRAS notification program, according to Austin Therrell, executive director of AAFCO and another panelist. “It’s essentially AAFCO self-affirmed GRAS, if you will,” he said, because the process will involve rigorous scientific review by a panel of experts.

“Someone who does a GRAS through our process would not need to submit it to FDA, because it’s voluntary at this point in time,” Therrell further explained, with a caveat related to the current situation related to possibly eliminating or reforming self-GRAS. “That conclusion from the expert panel would come back to the association, and we would ultimately vote on that recommendation from the expert panel. So once that happens, it would go through our process; we would publish it in our Official Publication (OP). Most of the state fee programs reference AAFCO terms and definitions, so that would give it legal standing in the states. But while it’s still meeting GRAS requirements, FDA would hopefully view that as self-affirmed GRAS.”

Therrell agreed with Harrison that current self-GRAS notifications are inconsistent, which causes issues for state feed regulators, the members of AAFCO. “There’s not a level of trust and transparency: Who did the expert panel reviews and who put the dossiers together?” Therrell explained. “It’s problematic that states don’t have the resources to review those dossiers that are self-concluded GRAS, and so the AAFCO process kind of solves that with having a little more oversight and having trust in KSU to make sure those expert panels are doing that work. Those dossiers are really in-depth.”

The PURR Act, on the other hand, would codify everything at the federal level, said Dana Brooks, president and CEO of the Pet Food Institute and the final panelist. “That’s part of what we did in the PURR Act, in recognition of the fact that we need to codify what’s already been approved through AAFCO, through chapter six and chapter five [of the OP], the things there that we make sure become federal GRAS,” she explained. “What’s done in the past becomes FDA-approved GRAS.”

FDA’s new AFIC program would offer official recognition and promises a 90-day turnaround, the availability of pre-consultation and enforcement discretion. Yet Harrison expressed deep skepticism about its potential given current agency constraints.

“I don’t see how FDA can both do the GRAS certification program and do the new consultation process in an effective and fast manner,” he warned, citing a 35% budget cut that has reduced reviewers from 33 to approximately 22. He added that the Center for Veterinary Medicine has historically been challenging and slow to work with, making the review process significantly more difficult than with FDA divisions overseeing human food.

These concerns might also apply to any new regulations or processes stemming from the PURR Act if it were passed. In addition, AAFCO and state regulators oppose the act because it would preempt them from having authority over ingredients in products sold in their states, Therrell said. “It would force a lot of our state programs to recognize those ingredients that have been self-concluded GRAS outside of the AAFCO process,” he explained, adding that chapter six of the OP contains only GRAS notifications submitted to and reviewed by FDA; it doesn’t include self-GRAS affirmations, which is why many states won’t recognize them.

Industry collaboration and cooperation recommended

Brooks said that the PURR Act and its potential to codify self-GRAS at the federal level, along with why animal food industries need the process, have been presented to Kennedy. That doesn’t mean she has much hope he or others will be swayed. “I sit here today feeling very confident, and who I know is leading this charge in the Senate and in Congress, that self-GRAS is going to go away,” she said. “Legislatively, it will pass.”

Yet Harrison proposed a sort of middle ground to possibly preserve self-GRAS. “Is there an opportunity to perhaps add some checks and balances there that would give the confidence that’s needed for Congressional members to consider?” he wondered. “It’s not an all or nothing. It is an opportunity, I think, for conversations about other ways to view GRAS.”

No matter what transpires regarding self-GRAS throughout the rest of this year and beyond, everyone would be wise to work together, all the panelists agreed. That means maintaining strong partnerships among industry, academia and government agencies while advocating for policies that support both innovation and consumer safety. As Harrison noted, “Regulation does not keep pace with innovation. Innovation is always outstripping regulation.” Adaptive and collaborative approaches are essential for the industry’s future.