There was a recent report of an increase in human food companies getting into the pet food business. Many of them likely assume the regulation of pet foods is the same if not less stringent than what they already face. It's one thing if it's a conglomerate buying an established pet food company, where it can rely on the experience of the existing personnel. However, when a human food company tries to enter the pet food market on its own, it may find some of the labeling regulations to be quite unexpected.

Differences in human and pet food labeling regulations

Foods for human consumption fall under the authority of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), with the primary exception of meat and poultry products regulated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Labels for products subject to USDA inspection must be approved by the agency, but FDA does not require premarket review of labeling. Rather it is the burden of the manufacturer to ensure the label is compliant. True, FDA may take action if it finds a food on the market that is not labeled in accordance with its regulations, but oversight is spotty.

On the other hand, in addition to FDA, the majority of states require submission of pet food labels as a condition of registration and/or licensure in that state. Although a state's authority stops at its border, in practice the objections of even a single state can have nation-wide consequences, as it is typically infeasible to have multiple labels on the market at once. Many human food companies are simply not ready for that.

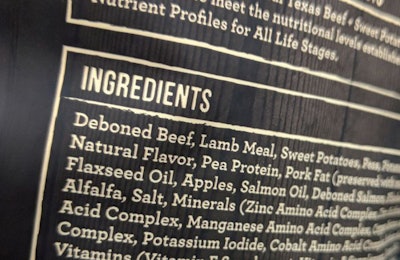

Many aspects of labeling are the same for both human and pet foods (e.g., net weight declaration, manufacturer's or distributor's name and address). However, as per the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990, labels for human foods must convey nutrient content information via a specifically formatted "Nutrition Facts Box." The same information on a pet food label, however, must meet the requirements of the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) model regulations. This is a decidedly different format, including a "guaranteed analysis" where nutrient content is expressed in terms of percentages, not per serving, along with a separate and distinct calorie content statement. Other aspects of pet food labeling as dictated by AAFCO, including the nutritional adequacy statement, have no equivalent counterpart in human food labeling.

AAFCO is exploring means to "modernize" pet food labeling and make it appear more like consumers may be used to when shopping for their own food. However, despite efforts to make the "Pet Nutrition Fact Box" outwardly appear similar, there will still be significant distinctions. Many of the remnants of current AAFCO labeling will remain, and human food companies would have to adjust accordingly.

Ingredient declarations and definitions

FDA regulations (for both human and pet food) only stipulate that ingredients be declared by their "common or usual" names. However, distinct to pet foods, AAFCO has defined many animal feed ingredients which, when applicable, must be declared by that exact name. Even when a food ingredient is subject to an FDA Standard of Identity where the components of that ingredient must be declared parenthetically, the terminology may be different. The ingredients that comprise yogurt, for example, may have to be declared by other names when converted to "AAFCO-speak."

Under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA), ingredients do not necessarily have to be GRAS (generally recognized as safe) substances or approved food additives if they meet the statutory definition of "dietary supplement" as intended for human consumption. While dietary supplements are still "foods," this law has allowed for a dramatic increase in the use of substances such as herbs and metabolites that normally wouldn't be allowed in a food in conventional form. Also, claims relating to effect on the structure or function of the body distinct from its nutritive value are generally tolerated on these labels. Regardless, DSHEA does not apply to animal products. Hence, the pre-DSHEA regulatory rubric remains for pet foods, and many human food manufacturers, especially dietary supplement manufacturers, find that the ingredients and claims they are used to making simply are not acceptable when it comes to a pet food.

The National Animal Supplement Council (NASC) has developed a means to label some pet products in a manner that effectively escapes scrutiny as an animal feed by most states. Labeled similarly to human supplements, they may contain ingredients or bear claims not normally allowed. However, there is a price, in that they cannot be represented as foods or to be of nutritional benefit and may be subject to regulation as "unapproved drugs of low regulatory priority." Hybrid products, i.e., those that contain both nutritional and non-nutritional components, are particularly problematic in terms of label compliance.

For more insights by Dr. Dzanis