Her childhood pet dog, Rusty, taught Jane Goodall that animals have minds and personalities, a lesson that conventional scientists would in turn learn from Goodall. She observed her pet pedagogue as he showed signs of emotions and individuality, among other attributes thought impossible in animals by academic dogma.

A few years ago, I saw Goodall tell stories of Rusty to a packed audience at Mizzou Arena in Columbia, Missouri. She recounted how she interacted with Rusty and saw behaviors that showed he was thinking with his own mind. At that time, this was scientific heresy. For most of science’s history, prevailing presumptions echoed preceding religious beliefs that animals and humans were categorically different. Biologists and anatomists often considered animals as little more than meat machines.

Now, decades later, both public and academic sentiment have changed to incorporate more respect for animals’ mental states. Along with that, pet humanization has become a dominant global market force for dog, cat and other pet food brands. In turn, pet food and treats may fuel further human empathy for wildlife, as pet owners interact with their pets like Goodall and Rusty did.

Pet humanization may influence empathy for wildlife

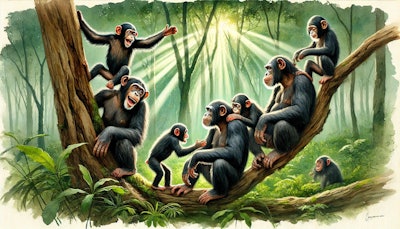

When Goodall was a child, in the 30’s and 40’s, researchers rejected evidence that other animals shared psychological characteristics with humans as anthropomorphism. Goodall’s interactions with Rusty offered her a contrasting, less dogmatic perspective on dogs. By the 1960’s, when Goodall began sharing her insights into the chimpanzee communities of Tanzania, most scientists still rejected the idea that animals and humans share mental similarities, despite all the biological ones.

Eventually, Goodall’s intricate documentation of ape behavior, both human and chimp, legitimized the idea that we differ only in degree, not in type. By bringing people into the world of chimps and other animals, Goodall made conservation personal by helping us identify with animals as more than resources or decorations, but as beings quite like us.

To put it in pet food industry jargon, humanization of pets led to revolutionary techniques in wild chimpanzee research and conservation. Think about how many other little Janes are learning to interact with the minds of their own pets today. What effect may that have on future conservation efforts, which are now even more crucial than when Dr. Goodall started her work?

I wonder if the humanization of pets would have become such a global force if people like Goodall and Dian Fossey, the late gorilla researcher who grew up riding horses, hadn’t provided empirical evidence of animals’ complex mental lives. Now that humanization of pets drives the global pet food industry, perhaps the industry helps to create a feedback loop of empathy for animals. Rusty learned tricks from young Goodall, and she made many observations on his intelligence while teaching him.

I don’t know what methods worked with Rusty, but I used treats as a positive reinforcement while teaching my childhood dog, Pepper. Perhaps, dog, cat and other pet foods and treats serve as a means for budding scientists and all other pet owners to observe and interact with the minds of other lifeforms. People report in surveys that pet meal times are a primary point of interaction with the animals, and that treats serve as expressions of love, not just training aids. After seeing emotional responses in a pet cat or dog, it doesn’t take a huge mental leap to see those same responses when we watch cheetahs or fennec foxes. We can’t all be Goodall, but at least our relationships with our pets builds our capacity for empathy with wildlife, something I believe we need abundantly in this age of mass extinction.