ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED Feb. 22, 2022

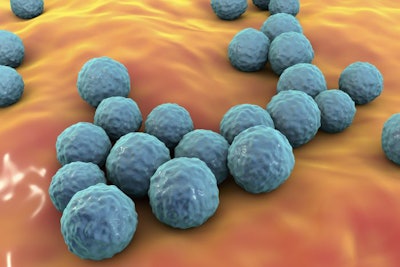

Microbiologists grew antibiotic-resistant Enterococcus bacteria found in samples of both dry and wet pet foods bought in Portugal. The microbes held genes granting resistance to clinically important drugs, such as linezolid and vancomycin. Although pet food hasn’t been documented passing these germs to people, a reservoir of antibiotic resistance genes could be created in the gut of dogs, study co-author Ana Freitas, Ph.D., assistant professor at the University Institute of Health Sciences (Instituto Universitário de Ciências da Saúde) in Portugal, said. That store of genes in the environment could potentially reach humans. The International Journal of Food Microbiology published her teams’ results in February.

The example of Salmonella, a true zoonotic bacteria, has already demonstrated this, she said.

“One problem is that the requirements of pet food do not include the screening of antibiotic-resistant bacteria such as Enterococci, just pathogenic bacteria like Salmonella or Campylobacter,” she said.

Antibiotic-resistant Enterococcus bacteria, including vancomycin-resistant strains, most frequently infect hospital patients and people with immune system issues. The bacteria cause thousands of deaths in the United States each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Study on antibiotic-resistant Enterococcus bacteria in pet food

Freitas’ study included 55 samples from 25 brands of which 21 were sold internationally. The products included 22 wet, 14 raw frozen, 8 dry, 7 treats and 4 semi-wet. The researchers bought the products from nine retail outlets in the Porto, Portugal region between September 2019 and January 2020.

The microbiologists tested the bacteria for resistance to 13 antibiotics. The scientists identified clinically-relevant species (E. faecium and E. faecalis), antibiotic resistance (vanA, vanB, optrA, poxtA) and virulence (e.g. ptsD, esp, sgrA) genes using polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Seven species of Enterococcus, mostly E. faecium and E. faecalis, occurred in 30 samples, representing 54% of the total. The scientists found the bacteria in 14 raw, 16 heat-treated, seven dry, six wet and three treats. E. faecium occurred most frequently in dry pet foods, with E. faecalis predominating in wet samples.

More than 40% of the bacteria taken from the pet foods were resistant to erythromycin, tetracycline, quinupristin-dalfopristin, streptomycin, gentamicin, chloramphenicol, ampicillin or ciprofloxacin. Lower rates of samples showed resistance to linezolid (23%; optrA, poxtA), or vancomycin and teicoplanin (2% each; vanA).

Multidrug-resistant samples (31%) mostly came from raw foods, although they were also taken from wet foods and treats.

“[In thermal processing,] Enterococcus are particularly resistant to temperature and dry conditions and not all bacteria will die, some will just stop their growth but can ‘resuscitate’ let's say when we give them proper conditions in the lab again,” she said. “That's why the more problematic bacteria were found in the raw dog food and less in the processed one.”